Hius 222 Book Review Paper Escape From Bataan

Coordinates: xv°thirty′34″Due north 121°02′40″E / fifteen.50944°Due north 121.04444°E / 15.50944; 121.04444

| Raid at Cabanatuan | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Pacific theater of Earth State of war II | |||||||

Former Cabanatuan POWs in celebration, January 30, 1945 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| | | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 133 U.S. soldiers from the sixth Ranger Battalion and Alamo Scouts 250–280 Filipino guerrillas | est. 220 Japanese guards and soldiers est. 1,000 Japanese well-nigh the military camp est. 5,000–eight,000 Japanese in Cabanatuan | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 2 killed 4 wounded 2 prisoners died ix wounded in activeness | 530–one,000+ killed 4 tanks out of activity | ||||||

The Raid at Cabanatuan (Filipino: Pagsalakay sa Cabanatuan), also known equally the Peachy Raid (Filipino: Ang Dakilang Pagsalakay), was a rescue of Centrolineal prisoners of state of war (POWs) and civilians from a Japanese camp near Cabanatuan, Nueva Ecija, Philippines. On Jan 30, 1945, during World War II, United States Army Rangers, Alamo Scouts and Filipino guerrillas liberated more than 500 from the Pw campsite.

After the surrender of tens of thousands of American troops during the Boxing of Bataan, many were sent to the Cabanatuan prison camp later the Bataan Death March. The Japanese shifted almost of the prisoners to other areas, leaving just over 500 American and other Allied POWs and civilians in the prison. Facing savage conditions including disease, torture, and malnourishment, the prisoners feared they would exist executed by their captors earlier the arrival of General Douglas MacArthur and his American forces returning to Luzon. In belatedly January 1945, a plan was developed by Sixth Army leaders and Filipino guerrillas to send a small force to rescue the prisoners. A grouping of over 100 rangers and scouts and 200 guerrillas traveled 30 miles (48 km) behind Japanese lines to achieve the campsite.

In a night raid, nether the cover of darkness and with distraction by a P-61 Black Widow night fighter, the group surprised the Japanese forces in and around the camp. Hundreds of Japanese troops were killed in the thirty-minute coordinated attack; the Americans suffered minimal casualties. The rangers, scouts, and guerrillas escorted the POWs back to American lines. The rescue immune the prisoners to tell of the death march and prison camp atrocities, which sparked a blitz of resolve for the war against Japan. The rescuers were awarded commendations by MacArthur, and were as well recognized by President Franklin D. Roosevelt. A memorial now sits on the site of the former military camp, and the events of the raid have been depicted in several films.

Groundwork [edit]

After the United states was attacked at Pearl Harbor on December vii, 1941 past Japanese forces, it entered World State of war II to bring together the Centrolineal forces in their fight against the Axis powers. American forces led past General Douglas MacArthur, already stationed in the Philippines as a deterrent against a Japanese invasion of the islands, were attacked by the Japanese hours afterwards Pearl Harbor. On March 12, 1942, General MacArthur and a few select officers, on the orders of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, left the American forces, promising to render with reinforcements. The 72,000 soldiers of the United States Army Forces in the Far East (USAFFE),[1] fighting with outdated weapons, lacking supplies, and stricken with disease and malnourishment, somewhen surrendered to the Japanese on April ix, 1942.[ii]

The Japanese had initially planned for only 10,000–25,000 American and Filipino prisoners of war (POWs). Although they had organized two hospitals, ample food, and guards for this guess, they were overwhelmed with over 72,000 prisoners.[2] [3] By the terminate of the threescore-mile (97-km) march, only 52,000 prisoners (approximately nine,200 American and 42,800 Filipino) reached Military camp O'Donnell, with an estimated 20,000 having died from illness, hunger, torture, or murder.[3] [4] [v] Later with the closure of Camp O'Donnell about of the imprisoned soldiers were transferred to the Cabanatuan prison camp to bring together the POWs from the Boxing of Corregidor.[6]

In 1944, when the United States landed on the Philippines to recapture it, orders had been sent out by the Japanese loftier control to kill the POWs in order to avoid them existence rescued by liberating forces. One method of the execution was to round the prisoners up in i location, pour gasoline over them, and so burn them live.[7] After hearing the accounts of the survivors from the massacre at the Puerto Princesa Prison house Camp, the liberating forces feared that the condom of the POWs existence held in the country was in jeopardy, and decided to launch a series of rescue operations to save the surviving POWs on the islands.

POW campsite [edit]

A old Pw's drawing of one prisoner giving a drinkable to another at the Cabanatuan campsite

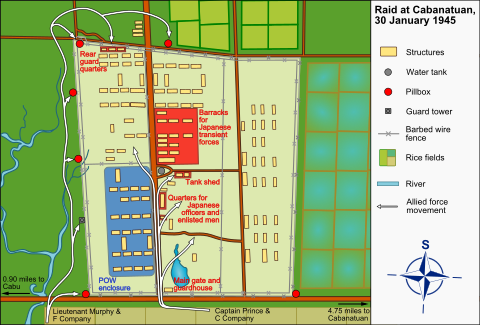

The Cabanatuan prison camp was named after the nearby city of 50,000 people (locals as well called it Military camp Pangatian, later a small nearby village).[6] [eight] The camp had starting time been used as an American Section of Agriculture station and so a preparation camp for the Filipino regular army.[ix] When the Japanese invaded the Philippines, they used the camp to house American POWs. It was one of three camps in the Cabanatuan area and was designated for holding ill detainees.[10] [eleven] Occupying virtually 100 acres (0.40 kmii), the rectangular-shaped camp was roughly 800 yards (730 m) deep by 600 yards (550 chiliad) across, divided by a road that ran through its center.[12] [13] [14] [xv] [16] Ane side of the camp housed Japanese guards, while the other included bamboo barracks for the prisoners as well as a department for a hospital.[eleven] Nicknamed the "Zero Ward" considering zero was the probability of getting out of it alive,[16] the infirmary housed the sickliest prisoners every bit they waited to die from diseases such every bit dysentery and malaria.[17] [18] 8-foot (2.four-m) high barbed wire fences surrounded the camp, in addition to multiple pillbox bunkers and four-story guard towers.[19] [xx] [21]

At its peak, the army camp held 8,000 American soldiers (along with a small number of soldiers and civilians from other nations including the Britain, Norway, and kingdom of the netherlands), making it the largest Pw military camp in the Philippines.[22] [23] This number dropped significantly as athletic soldiers were shipped to other areas in the Philippines, Japan, Japanese-occupied Taiwan, and Manchukuo to piece of work in slave labor camps. Every bit Nippon had not ratified the Geneva Convention, the POWs were transported out of the camp and forced to work in factories to build Japanese weaponry, unload ships, and repair airfields.[24] [25]

The imprisoned soldiers received two meals a day of steamed rice, occasionally accompanied past fruit, soup, or meat.[26] To supplement their nutrition, prisoners were able to smuggle nutrient and supplies hidden in their underwear into the army camp during Japanese-approved trips to Cabanatuan. To forestall extra nutrient, jewelry, diaries, and other valuables from beingness confiscated, items were hidden in clothing or latrines, or were buried earlier scheduled inspections.[27] [28] Prisoners collected food using a variety of methods including stealing, bribing guards, planting gardens, and killing animals which entered the military camp such as mice, snakes, ducks, and stray dogs.[29] [thirty] [31] The Filipino surreptitious nerveless thousands of quinine tablets to smuggle into the camp to treat malaria, saving hundreds of lives.[32] [33]

One group of Corregidor prisoners, before first entering the camp, had each hidden a piece of a radio nether their wearable, to later be reassembled into a working device.[34] When the Japanese had an American radio technician fix their radios, he stole parts. The prisoners thus had several radios to mind to newscasts on radio stations every bit far away as San Francisco, allowing the POWs to hear about the status of the war.[35] [36] [37] A smuggled camera was used to document the camp'southward living conditions.[38] Prisoners also constructed weapons and smuggled armament into the camp for the possibility of securing a handgun.[39]

A hut used to firm prisoners in the camp

Multiple escape attempts were made throughout the history of the prison house camp, but the majority ended in failure. In i attempt, four soldiers were recaptured past the Japanese. The guards forced all prisoners to watch as the four soldiers were beaten, forced to dig their own graves and and then executed.[40] Presently thereafter, the guards put upwards signs declaring that if other escape attempts were made, ten prisoners would exist executed for every escapee.[40] [41] Prisoners' living quarters were so divided into groups of 10, which motivated the POWs to keep a shut heart on others to foreclose them from making escape attempts.[twoscore] [42]

The Japanese permitted the POWs to build septic systems and irrigation ditches throughout the prisoner side of the camp.[43] [44] An onsite commissary was available to sell items such as bananas, eggs, coffee, notebooks, and cigarettes.[45] Recreational activities allowed for baseball, horseshoes, and ping pong matches. In addition, a 3,000-volume library was immune (much of which was provided by the Red Cross), and films were shown occasionally.[43] [46] [47] A bulldog was kept by the prisoners, and served as a mascot for the camp.[48] Each year effectually Christmas, the Japanese guards gave permission for the Red Cross to donate a small-scale box to each of the prisoners, containing items such as corned beef, instant coffee, and tobacco.[38] [49] [fifty] Prisoners were also able to send postcards to relatives, although they were censored by the guards.[50] [51]

Equally American forces continued to arroyo Luzon, the Japanese Imperial General Headquarters ordered that all athletic POWs be transported to Japan. From the Cabanatuan camp, over 1,600 soldiers were removed in October 1944, leaving over 500 sick, weak, or disabled POWs.[52] [53] [54] On January vi, 1945, all of the guards withdrew from the Cabanatuan camp, leaving the POWs lonely.[55] The guards had previously told prisoner leaders that they should not attempt to escape, or else they would be killed.[56] When the guards left, the prisoners heeded the threat, fearing that the Japanese were waiting near the camp and would use the attempted escape as an excuse to execute them all.[56] Instead, the prisoners went to the guards' side of the military camp and ransacked the Japanese buildings for supplies and big amounts of nutrient.[55] Prisoners were alone for a couple of weeks, except when retreating Japanese forces would periodically stay in the camp. The soldiers mainly ignored the POWs, except to inquire for food. Although aware of the potential consequences, the prisoners sent a minor group exterior the prison's gates to bring in two carabaos to slaughter. The meat from the animals, along with the food secured from the Japanese side of the military camp, helped many of the POWs to regain their strength, weight, and stamina.[57] [58] [59] In mid-Jan, a large group of Japanese troops entered the camp and returned the prisoners to their side of the camp.[lx] The prisoners, fueled by rumors, speculated that they would soon be executed by the Japanese.[61]

Planning and preparation [edit]

On Oct 20, 1944, Full general Douglas MacArthur's forces landed on Leyte, paving the style for the liberation of the Philippines. Several months afterward, as the Americans consolidated their forces to set for the main invasion of Luzon, well-nigh 150 Americans were executed by their Japanese captors on December 14, 1944 at the Puerto Princesa Prison Camp on the isle of Palawan. An air raid warning was sounded so that the inmates would enter slit-trench and log-and-earth covered air-raid shelters, and at that place doused with gasoline and burned live.[62] One of the survivors, PFC Eugene Nielsen, recounted his tale to U.S. Regular army Intelligence on January 7, 1945.[63] Two days afterwards, MacArthur's forces landed on Luzon and began a rapid accelerate towards the capital, Manila.[64]

Major Robert Lapham, the American USAFFE senior guerrilla chief, and another guerrilla leader, Helm Juan Pajota, had considered freeing the prisoners within the camp,[65] simply feared logistical problems with hiding and caring for the prisoners.[66] An earlier program had been proposed by Lieutenant Colonel Bernard Anderson, leader of the guerrillas near the campsite. He suggested that the guerrillas would secure the prisoners, escort them 50 miles (80 km) to Debut Bay, and transport them using 30 submarines. The program was denied approval equally MacArthur feared the Japanese would catch up with the fleeing prisoners and impale them all.[12] In add-on, the Navy did not have the required submarines, particularly with MacArthur's upcoming invasion of Luzon.[65]

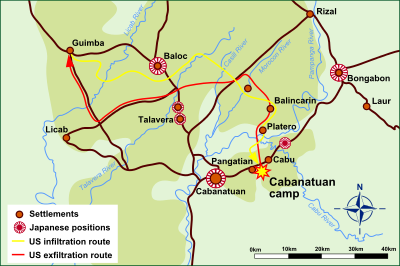

On Jan 26, 1945, Lapham traveled from his location near the prison army camp to Sixth Army headquarters, 30 miles (48 km) away.[67] He proposed to Lieutenant General Walter Krueger'due south intelligence chief Colonel Horton White that a rescue attempt be made to liberate the estimated 500 POWs at the Cabanatuan prison house army camp before the Japanese mayhap killed them all.[67] Lapham estimated Japanese forces to include 100–300 soldiers inside the camp, 1,000 across the Cabu River northeast of the camp, and possibly around v,000 inside Cabanatuan City.[67] Pictures of the camp were also available, every bit planes had taken surveillance images as recently equally January 19.[68] White estimated that the I Corps would not achieve Cabanatuan City until January 31 or February one, and that if any rescue attempt were to exist made, it would take to be on Jan 29.[69] White reported the details to Krueger, who gave the order for the rescue attempt.[67]

White gathered Lt. Col. Henry Mucci, leader of the 6th Ranger Battalion, and three lieutenants from the Alamo Scouts—the special reconnaissance unit attached to his Sixth Army—for a briefing on the mission to raid Cabanatuan and rescue the POWs.[67] The group developed a plan to rescue the prisoners. Fourteen Scouts, made upward of two teams, would leave 24 hours alee of the main force, to survey the camp.[seventy] The main force would consist of ninety Rangers from C Visitor and 30 from F Company who would march 30 miles backside Japanese lines, environs the army camp, kill the guards, and rescue and escort the prisoners back to American lines.[67] [71] The Americans would bring together up with 80 Filipino guerrillas, who would serve every bit guides and help in the rescue endeavour.[72] The initial plan was to set on the camp at 17:30 PST (UTC+8) on January 29.[73]

On the evening of Jan 27, the Rangers studied air reconnaissance photos and listened to guerrilla intelligence on the prison campsite.[74] The 2 five-man teams of Alamo Scouts, led by 1st Lts. William Nellist and Thomas Rounsaville, left Guimba at 19:00 and infiltrated behind enemy lines for the long expedition to attempt a reconnaissance of the prison camp.[75] [76] [77] Each Scout was armed with a .45 pistol, three mitt grenades, a burglarize or M1 carbine, a knife, and extra ammunition.[74] The next morn, the Scouts linked up with several Filipino guerrilla units at the village of Platero, ii miles (3.two km) north of the campsite.

The Rangers were armed with contrasted Thompson submachine guns, BARs, M1 Garand rifles, pistols, grenades, knives, and extra ammunition, besides as a few bazookas.[78] [79] Four combat photographers from a unit of the 832nd Signal Service Battalion volunteered to accompany the Scouts and Rangers to record the rescue after Mucci suggested the idea of documenting the raid.[80] Each photographer was armed with a pistol.[81] Surgeon Captain Jimmy Fisher and his medics each carried pistols and carbines.[78] [79] To maintain a link between the raiding group and Ground forces Command, a radio outpost was established outside of Guimba. The force had two radios, but their use was only approved in requesting air support if they ran into big Japanese forces or if there were last-minute changes to the raid (as well as calling off friendly fire by American shipping).[70] [78]

Behind enemy lines [edit]

The Rangers, Scouts, and guerrillas trekked through diverse terrain and crossed several rivers on their way to the prison army camp

Presently after 05:00 on January 28, Mucci and a reinforced company of 121 Rangers[fourscore] [82] [83] nether Capt. Robert Prince drove sixty miles (97 km) to Guimba, before slipping through Japanese lines at just after xiv:00.[78] [84] Guided past Filipino guerrillas, the Rangers hiked through open grasslands to avoid enemy patrols.[67] In villages along the Rangers' route, other guerrillas assisted in muzzling dogs and putting chickens in cages to forestall the Japanese from hearing the traveling grouping.[85] At one point, the Rangers narrowly avoided a Japanese tank on the national highway past following a ravine that ran under the road.[86] [87] [88]

The group reached Balincarin, a barrio (suburb) v miles (8.0 km) northward of the army camp, the following morning.[89] Mucci linked upward with Scouts Nellist and Rounsaville to go over the camp reconnaissance from the previous nighttime. The Scouts revealed that the terrain around the campsite was apartment, which would leave the force exposed earlier the raid.[89] Mucci also met with USAFFE guerrilla Captain Juan Pajota and his 200 men, whose intimate knowledge of enemy activity, the locals, and the terrain proved crucial.[90] Upon learning that Mucci wanted to button through with the set on that evening, Pajota resisted, insisting that it would exist suicide. He revealed that the guerrillas had been watching an estimated 1,000 Japanese soldiers camped out beyond the Cabu River simply a few hundred yards from the prison.[91] Pajota also confirmed reports that as many every bit seven,000 enemy troops were deployed effectually Cabanatuan Metropolis located several miles abroad.[92] With the invading American forces from the southwest, a Japanese division was withdrawing to the due north on a road close to the camp.[93] [94] He recommended waiting for the sectionalization to pass then that the strength would face minimal opposition. Afterward consolidating information from Pajota and the Alamo Scouts almost heavy enemy activity in the army camp area, Mucci agreed to postpone the raid for 24 hours,[93] and alerted the 6th Ground forces Headquarters to the development past radio.[95] He directed the Scouts to render to the camp and gain additional intelligence, especially on the strength of the guards and the exact location of the captive soldiers. The Rangers withdrew to Platero, a barrio 2.5 miles (four.0 km) south of Balincarin.[93]

Strategy [edit]

"We couldn't rehearse this. Anything of this nature, you'd ordinarily want to practice it over and over for weeks in accelerate. Get more information, build models, and discuss all of the contingencies. Work out all of the kinks. Nosotros didn't have time for whatsoever of that. Information technology was at present, or not."

—Capt. Prince reflecting on the fourth dimension constraints on planning the raid[96]

At 11:thirty on January 30, Alamo Scouts Lt. Beak Nellist and Pvt. Rufo Vaquilar, bearded equally locals, managed to gain access to an abandoned shack 300 yards (270 m) from the camp.[75] [97] Avoiding detection by the Japanese guards, they observed the camp from the shack and prepared a detailed report on the camp's major features, including the master gate, Japanese troop strength, the location of telephone wires, and the all-time attack routes.[13] [98] Shortly thereafter they were joined by 3 other Scouts, whom Nellist tasked to deliver the study to Mucci.[99] Nellist and Vaquilar remained in the shack until the showtime of the raid.[100]

Mucci had already been given Nellist's Jan 29 afternoon study and forwarded it to Prince, whom he entrusted to determine how to get the Rangers in and out of the chemical compound apace, and with as few casualties as possible. Prince developed a plan, which was so modified in light of the new written report from the abandoned shack reconnaissance received at 14:30.[101] He proposed that the Rangers would exist divide into two groups: well-nigh 90 Rangers of C Company, led by Prince, would assail the main camp and escort the prisoners out, while 30 Rangers of a platoon from F Company, allowable by Lt. John White potato, would point the first of the set on by firing into diverse Japanese positions at the rear of the camp at 19:thirty.[102] [103] Prince predicted that the raid would be achieved in 30 minutes or less. In one case Prince had ensured that all of the POWs were safely out of the military camp, he would fire a ruby flare, indicating that all troops should fall back to a meetup at Pampanga River 1.5 miles (2.4 km) n of the camp where 150 guerrillas would be fix with carabao-pulled carts to ship the POWs.[104] This group would help to load the POWs and escort them dorsum to American lines.

Captains Jimmy Fisher and Robert Prince and several Filipino guerrillas a few hours earlier the start of the raid

Ane of Prince's main concerns was the flatness of the countryside. The Japanese had kept the terrain clear of vegetation to ensure that approaching guerrilla attacks could be seen too as to spot prisoner escapes.[viii] Prince knew his Rangers would have to crawl through a long, open field on their bellies, correct nether the eyes of the Japanese guards. There would merely be just over an 60 minutes of full darkness, as the sun set up below the horizon and the moon rose.[8] This would still present the possibility of the Japanese guards noticing their motility, particularly with a nearly full moon. If the Rangers were discovered, the only planned response was for everyone to immediately stand and rush the army camp.[105] [106] The Rangers were unaware that the Japanese did non accept any searchlights that could be used to illuminate the perimeter.[107] Pajota suggested that to distract the guards, a United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) airplane should buzz the camp to divert the guards' eyes to the sky. Mucci agreed with the idea and a radio request was sent to command to enquire for a plane to fly over the campsite while the men fabricated their style across the field.[108] In preparation for possible injuries or wounds received during the encounter with the Japanese, the battalion surgeon, Cpt. Jimmy Fisher, developed a makeshift infirmary in the Platero school.[109]

By dawn on January 30, the road in front of the military camp was articulate of traveling Japanese troops.[110] Mucci fabricated plans to protect the POWs once they were freed from the campsite. Two groups of guerrillas of the Luzon Guerrilla Armed forces, 1 under Pajota and another under Capt. Eduardo Joson,[111] would be sent in reverse directions to hold the main route near the army camp. Pajota and 200 guerrillas were to set upward a roadblock next to the wooden bridge over the Cabu River.[104] [112] This setup, northeast of the prisoner military camp, would be the outset line of defense against the Japanese forces camped across the river, which would be inside earshot of the attack on the camp. Joson and his 75 guerrillas, along with a Ranger bazooka team, would gear up upwards a roadblock 800 yards (730 chiliad) southwest of the prisoner camp to stop whatsoever Japanese forces that would arrive from Cabanatuan.[104] Both groups would each identify 25 land mines in front of their positions, and i guerrilla from each group was given a bazooka to destroy any armored vehicles.[104] After the POWs and the residuum of the attacking force had reached the Pampanga River meeting point, Prince would fire a second flare to indicate to the ambush sites to pull back (gradually, if they faced opposition) and head to Platero.[103]

As the POWs had no knowledge of the upcoming assail, they went through their normal routine that nighttime. The previous day, 2 Filipino boys had thrown rocks into the prisoner side of the campsite with notes attached, "Exist set up to get out."[113] Bold that the boys were pulling a prank, the POWs disregarded the notes. The POWs were becoming more wary of the Japanese guards, believing that someday in the side by side few days they could be massacred for whatsoever reason. They figured that the Japanese would non want them to be rescued past advancing American forces, regain their strength, and return to fight the Japanese over again. In addition, the Japanese could impale the prisoners to prevent them from telling of the atrocities of the Bataan Death March or the weather condition in the campsite.[114] With the limited Japanese baby-sit, a small group of prisoners had already decided that they would make an escape endeavor at about xx:00.[115] [116]

Prisoner rescue [edit]

A P-61 Black Widow, similar to the 1 that distracted Japanese guards as American forces crawled towards the camp

At 17:00, a few hours after Mucci approved Prince's program, the Rangers departed from Platero. White cloths were tied effectually their left arms to prevent friendly fire casualties.[117] They crossed the Pampanga River and then, at 17:45, Prince and Murphy's men parted means to surround the camp.[102] [115] Pajota, Joson, and their guerrilla forces each headed to their ambush sites. The Rangers under Prince made their way to the primary gate and stopped nearly 700 yards (640 one thousand) from the camp to look for nightfall and the aircraft distraction.[115]

Meanwhile, a P-61 Blackness Widow from the 547th Night Fighter Squadron, named Hard to Get, had taken off at 18:00, piloted by Capt. Kenneth Schrieber and 1st Lt. Bonnie Rucks.[118] About 45 minutes earlier the attack, Schrieber cutting the power to the left engine at ane,500 feet (460 grand) over the camp. He restarted it, creating a loud backlash, and repeated the procedure twice more, losing altitude to 200 anxiety (61 m). Pretending that his plane was crippled, Schrieber headed toward depression hills, clearing them past a mere thirty feet (ix.ane k). To the Japanese observers, it seemed the aeroplane had crashed and they watched, waiting for a fiery explosion. Schrieber repeated this several times while too performing various aerobatic maneuvers. The ruse continued for 20 minutes, creating a diversion for the Rangers inching their style toward the military camp on their bellies.[118] [119] Prince afterwards commended the pilots' deportment: "The idea of an aerial decoy was a picayune unusual and honestly, I didn't think information technology would work, not in a meg years. But the pilot's maneuvers were so skillful and deceptive that the diversion was consummate. I don't know where we would take been without it."[118] Equally the plane buzzed the army camp, Lt. Carlos Tombo and his guerrillas forth with a small number of Rangers cut the campsite's telephone lines to preclude communication with the large strength stationed in Cabanatuan.[103]

Captain Pajota's guerrillas at Cabanatuan

At 19:xl, the whole prison house compound erupted into small arms burn down when Irish potato and his men fired on the guard towers and barracks.[120] Within the start fifteen seconds, all of the camp's baby-sit towers and pillboxes were targeted and destroyed.[121] Sgt. Ted Richardson rushed to shoot a padlock off of the main gate using his .45 pistol.[121] [122] The Rangers at the principal gate maneuvered to bring the guard barracks and officer quarters under fire, while the ones at the rear eliminated the enemy nearly the prisoners' huts and and then proceeded with the evacuation. A bazooka team from F Company ran upwards the main road to a tin shack which the Scouts had told Mucci held tanks. Although Japanese soldiers attempted to escape with two trucks, the team was able to destroy the trucks and then the shack.[123] [124]

At the beginning of the gunfire, many of the prisoners thought that it was the Japanese offset to massacre them.[125] One prisoner stated that the attack sounded similar "whistling slugs, Roman candles, and flaming meteors sailing over our heads."[126] Prisoners immediately hid in their shacks, latrines, and irrigation ditches.[126]

When the Rangers yelled to the POWs to come out and exist rescued, many of the POWs feared that it was the Japanese attempting to pull a fast one on them into being killed.[127] Besides, a substantial number resisted because the Rangers' weapons and uniforms looked nothing similar those of a few years earlier; for example, the Rangers wore caps, earlier soldiers had M1917 Helmets and coincidentally, the Japanese also wore caps.[128] [129] The Rangers were challenged by the POWs and asked who they were and where they were from. Rangers sometimes had to resort to physical strength to remove the detainees, throwing or boot them out.[130] Some of the POWs weighed so little due to illness and malnourishment that several Rangers carried two men on their backs.[131] Once out of the barracks, they were told past the Rangers to proceed to the chief, or forepart gate. Prisoners were disoriented considering the "main gate" meant the entrance to the American side of the campsite.[132] POWs collided with each other in the defoliation but were eventually led out past the Rangers.

A lone Japanese soldier was able to burn off iii mortar rounds toward the main gate. Although members of F Company quickly located the soldier and killed him, several Rangers, Scouts, and POWs were wounded in the attack.[133] [134] Battalion surgeon Capt. James Fisher was mortally injured in the breadbasket and was carried to the nearby village of Balincari.[135] Sentry Alfred Alfonso had a shrapnel wound to his abdomen.[136] [137] Spotter Lt. Tom Rounsaville and Ranger Pvt. 1st Class Jack Peters were also wounded by the avalanche.[136]

Illustration of the layout of the camp and the positions of the attacking American forces

A few seconds afterwards Pajota and his men heard Irish potato burn down the get-go shot, they fired on the alerted Japanese contingent situated across the Cabu River.[138] [139] Pajota had earlier sent a demolitions expert to set charges on the unguarded span to go off at 19:45.[112] [140] The bomb detonated at the designated time, and although it did not destroy the bridge, it formed a large pigsty over which tanks and other vehicles could non laissez passer.[141] [142] Waves of Japanese troops rushed the span, but the Five-shaped choke betoken created by the Filipino guerrillas repulsed each assault.[124] I guerrilla, who had been trained to employ the bazooka just a few hours earlier by the Rangers, destroyed or disabled 4 tanks that were hiding behind a clump of trees.[143] A grouping of Japanese soldiers made an effort to flank the deadfall position by crossing the river abroad from the bridge, but the guerrillas spotted and eliminated them.[143]

At 20:15, the camp was secured from the Japanese and Prince fired his flare to indicate the end of the assail.[144] No gunfire had occurred for the final fifteen minutes.[145] However, equally the Rangers headed towards the meetup, Cpl. Roy Sweezy was shot twice by friendly fire, and later died.[146] The Rangers and the weary, frail, and disease-ridden POWs made their mode to the appointed Pampanga River rendezvous, where a caravan of 26 carabao carts waited to send them to Platero, driven by local villagers organized by Pajota.[147] At xx:40, one time Prince determined that everyone had crossed the Pampanga River, he fired his second flare to indicate to Pajota and Joson's men to withdraw.[148] The Scouts stayed behind at the meetup to survey the expanse for enemy retaliatory movements.[149] Meanwhile, Pajota's men connected to resist the attacking enemy until they could finally withdraw at 22:00, when the Japanese forces stopped charging the bridge.[150] Joson and his men met no opposition, and they returned to assistance escort the POWs.[151]

Although the gainsay photographers were able to shoot images of the trek to and from the military camp, they were unable to apply their cameras during the night-fourth dimension raid, as the flashes would bespeak their positions to the Japanese.[152] One of the photographers reflected on the nighttime hindrance: "We felt like an eager soldier who had carried his rifle for long distances into one of the war's most crucial battles, and then never got a chance to fire information technology."[103] The Signal Corps photographers instead assisted with escorting the POWs out of the camp.[152]

Expedition to American lines [edit]

"I fabricated the Decease March from Bataan, so I tin can certainly make this one!"

—one of the POWs during the trek back to American lines[153]

By 22:00, the Rangers and ex-POWs arrived at Platero, where they rested for half an hour.[149] [151] [154] A radio message was sent and received by Sixth Army at 23:00 that the mission had been a success, and that they were returning with the rescued prisoners to American lines.[155] Afterwards a headcount, it was discovered that POW Edwin Rose, a deaf British soldier, was missing.[156] Mucci dictated that none of the Rangers could be spared to search for him, so he sent several guerrillas to do then in the morning.[156] It was later learned that Rose had fallen asleep in the latrine before the attack.[141] Rose woke early on the next morning, and realized the other prisoners were gone and that he was left behind. Even so, he took the fourth dimension to shave and put on his best wearing apparel that he had been saving for the day he would be rescued. He walked out of the prison house military camp, thinking that he would soon be constitute and led to freedom. Certain plenty, Rose was constitute by passing guerrillas.[157] [158] Arrangements were made for a tank destroyer unit of measurement to selection him upwardly and send him to a hospital.[159]

Former Cabanatuan POWs marching to American lines

In a makeshift hospital at Platero, Lookout Alfonso and Ranger Fisher were rapidly put into surgery. The shrapnel was removed from Alfonso'southward abdomen, and he was expected to recover if returned to American lines. Fisher's shrapnel was too removed, but with express supplies and widespread damage to both his tum and intestines, it was decided more than all-encompassing surgery would need to be completed in an American hospital.[153] [160] Mucci ordered that an airstrip exist built in a field next to Platero and then that a plane could airlift him to American lines. Some Scouts and freed prisoners stayed behind to construct the airstrip.

As the group left Platero at 22:thirty to trek back towards American lines, Pajota and his guerrillas continually sought out local villagers to provide additional carabao carts to transport the weakened prisoners.[147] The majority of the prisoners had little or no clothing and shoes, and information technology became increasingly hard for them to walk.[161] When the group reached Balincarin, they had accumulated about 50 carts.[162] Despite the convenience of using the carts, the carabao traveled at a sluggish footstep, only 2 miles per hour (three.2 km/h), which greatly reduced the speed of the return trip.[149] By the time the group reached American lines, 106 carts were being used.[163]

In addition to the tired former prisoners and civilians, the majority of the Rangers had simply slept for five to six hours over the by iii days. The soldiers oftentimes had hallucinations or vicious comatose as they marched. Benzedrine was distributed by the medics to keep the Rangers active during the long march. One Ranger commented on the effect of the drug: "It felt like your eyes were popped open. Y'all couldn't have closed them if y'all wanted to. One pill was all I ever took—it was all I ever needed."[164]

P-61 Blackness Widows again helped the group by patrolling the path they took on its way dorsum to American lines. At 21:00, i of the aircraft destroyed 5 Japanese trucks and a tank located on a road 14 miles (23 km) from Platero that the group would later travel on.[153] The group was also met by circling P-51 Mustangs that guarded them as they neared American lines. The freed prisoner George Steiner stated that they were "jubilant over the appearance of our airplanes, and the audio of their strafing was music to our ears".[157]

Different routes were used for the infiltration and extraction behind Japanese lines

During one leg of the return trip, the men were stopped past the Hukbalahap, Filipino Communist guerrillas who hated both the Americans and the Japanese. They were also rivals to Pajota's men. One of Pajota's lieutenants conferred with the Hukbalahap and returned to tell Mucci that they were not allowed to pass through the hamlet. Angered by the message, Mucci sent the lieutenant dorsum to insist that pursuing Japanese forces would be coming. The lieutenant came back and told Mucci that only Americans could pass, and Pajota's men had to stay. Both the Rangers and guerrillas were finally allowed through after an agitated Mucci told the lieutenant that he would call in an artillery barrage and level the whole village. In fact, Mucci'due south radio was not working at that point.[165]

Carabao cart like to those used in the expedition to American lines

At 08:00 on January 31, Mucci's radioman was able to finally contact Sixth Army headquarters. Mucci was directed to go to Talavera, a town captured past the Sixth Regular army eleven miles (18 km) from Mucci'due south current position.[163] At Talavera, the freed soldiers and civilians boarded trucks and ambulances for the last leg of their journey dwelling.[166] The POWs were deloused, and given hot showers and new clothes.[167] At the POW hospital, one of the Rangers was reunited with his rescued begetter, who had been assumed killed in combat three years before.[168] The Scouts and the remaining POWs who had stayed backside to go James Fisher onto a plane also encountered resistance by the Hukbalahap.[169] After threatening the communist band, the Scouts and POWs were granted condom passage and reached Talavera on February 1.[169]

A few days after the raid, Sixth Army troops inspected the camp. They collected a large number of expiry certificates and cemetery layouts,[159] as well every bit diaries, poems, and sketchbooks.[158] The American soldiers too paid 5 pesos to each of the carabao cart drivers who had helped to evacuate the POWs.[159] [170]

Outcome and historical significance [edit]

| Prisoners rescued [171] | |

| American soldiers | 464 |

| British soldiers | 22 |

| Dutch soldiers | three |

| American civilians | 28 |

| Norwegian civilians | two |

| British civilian | 1 |

| Canadian civilian | i |

| Filipino civilian | 1 |

| Full | 522 |

The raid was considered successful—489 POWs were liberated, along with 33 civilians. The total included 492 Americans, 23 British, three Dutch, ii Norwegians, one Canadian, and one Filipino.[171] The rescue, along with the liberation of Campsite O'Donnell the same 24-hour interval, allowed the prisoners to tell of the Bataan and Corregidor atrocities, which sparked a new moving ridge of resolve for the state of war against Nihon.[172] [173]

Prince gave a great deal of credit for the success of the raid to others: "Any success nosotros had was due non only to our efforts but to the Alamo Scouts and Air Force. The pilots (Capt. Kenneth R. Schrieber and Lt. Bonnie B. Rucks) of the aeroplane that flew and then low over the army camp were incredibly dauntless men."[174]

Some of the Rangers and Scouts went on bond drive tours around the United States and too met with President Franklin D. Roosevelt.[170] [172] In 1948, the United States Congress created legislation which provided $i ($eleven.28 today) for each day the POWs had been held in a prisoner camp, including Cabanatuan.[175] Two years later, Congress once again approved an additional $1.fifty per day (a combined total of $28.xvi in 1994 terms).[175]

Estimates of the Japanese soldiers killed during the attack ranged from 530 to 1,000.[167] [172] The estimates include the 73 guards and approximately 150 traveling Japanese who stayed in the camp that night, likewise as those killed by Pajota's men attempting to cross the Cabu River.[21] [176] [177]

Several Americans died during and after the raid. A prisoner weakened by affliction died of a centre attack every bit a Ranger carried him from the barracks to the main gate.[178] [179] The Ranger later recalled, "The excitement had been as well much for him, I guess. It was really sad. He was merely a hundred anxiety from the liberty he had non known for nearly three years."[178] Another prisoner died of illness only equally the grouping had reached Talavera.[180] Although Mucci had ordered that an airstrip be built in a field next to Platero so that a aeroplane could evacuate Fisher to get medical attention, it was never dispatched, and he died the next twenty-four hours.[181] His concluding words were "Good luck on the way out."[182] The other Ranger killed during the raid was Sweezy, who was struck in the back by ii rounds from friendly fire. Both Fisher and Sweezy are buried at Manila National Cemetery. Twenty of Pajota's guerrillas were injured, equally were two Scouts and ii Rangers.[167] [172]

Alamo Scouts afterwards the raid

The American prisoners were quickly returned to the United States, most by aeroplane. Those who were still sick or weakened remained at American hospitals to continue to recuperate. On February 11, 1945, 280 POWs left Leyte aboard the transport USS Full general A.E. Anderson bound for San Francisco via Hollandia, New Guinea.[183] In an effort to counter the improved American morale, Japanese propaganda radio announcers circulate to American soldiers that submarines, ships, and planes were hunting the General Anderson.[184] The threats proved to exist a bluff, and the ship safely arrived in San Francisco Bay on March 8, 1945.[185]

News of the rescue was released to the public on February 2.[186] The feat was celebrated by MacArthur'south soldiers, Allied correspondents, and the American public, as the raid had touched an emotional chord amid Americans concerned virtually the fate of the defenders of Bataan and Corregidor. Family unit members of the POWs were contacted by telegram to inform them of the rescue.[187] News of the raid was broadcast on numerous radio outlets and newspaper front pages.[188] The Rangers and POWs were interviewed to describe the atmospheric condition of the army camp, likewise every bit the events of the raid.[189] The enthusiasm over the raid was later overshadowed by other Pacific events, including the Boxing for Iwo Jima and the dropping of the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.[173] [190] The raid was presently followed by additional successful raids, such equally the raid of Santo Tomas Civilian Internment Camp on February 3,[191] the raid of Bilibid Prison on Feb 4,[192] and the raid at Los Baños on February 23.[193]

Former Cabanatuan POWs at a makeshift hospital in Talavera

A Sixth Army study indicated that the raid demonstrated " ... what patrols can accomplish in enemy territory by post-obit the basic principles of scouting and patrolling, 'sneaking and peeping,' [the] use of concealment, reconnaissance of routes from photographs and maps prior to the actual operation, ... and the coordination of all arms in the accomplishment of a mission."[194] MacArthur spoke nigh his reaction to the raid: "No incident of the campaign in the Pacific has given me such satisfaction as the release of the POWs at Cabanatuan. The mission was brilliantly successful."[195] He presented awards to the soldiers who participated in the raid on March 3, 1945. Although Mucci was nominated for the Medal of Honor, he and Prince both received Distinguished Service Crosses. Mucci was promoted to colonel and was given command of the 1st Regiment of the 6th Infantry Sectionalization.[175] All other American officers and selected enlisted received Silver Stars.[196] The remaining American enlisted men and the Filipino guerrilla officers were awarded Bronze Stars.[196] Nellist, Rounsaville, and the other twelve Scouts received Presidential Unit Citations.[197]

In tardily 1945, the bodies of the American troops who died at the camp were exhumed, and the men moved to other cemeteries.[198] Land was donated in the late 1990s by the Filipino government to create a memorial. The site of the Cabanatuan camp is now a park that includes a memorial wall listing the 2,656 American prisoners who died there.[199] The memorial was financed by former American POWs and veterans, and is maintained past the American Battle Monuments Commission.[198] [200] A joint resolution past Congress and President Ronald Reagan designated April 12, 1982 as "American Salute to Cabanatuan Prisoner of War Memorial Twenty-four hour period".[201] In Cabanatuan Urban center, a hospital is named for guerrilla leader Eduardo Joson.[200]

Depictions in motion picture [edit]

"People everywhere try to thank united states of america. I think the thank you should go the other way. I'll be grateful for the remainder of my life that I had a gamble to exercise something in this state of war that was not subversive. Nothing for me tin ever compare with the satisfaction I got from helping to complimentary our prisoners."

—Capt. Prince, reflecting on the public reaction to the mission[202]

Several films have focused on the raid, while besides including archival footage of the POWs.[203] Edward Dmytryk's 1945 movie Back to Bataan, starring John Wayne, opens by retelling the story of the raid on the Cabanatuan Pw army camp-with real life film of the POW survivors. In July 2003, the PBS documentary program American Experience aired an hr-long film about the raid, titled Bataan Rescue. Based on the books The Great Raid on Cabanatuan and Ghost Soldiers, the 2005 John Dahl film The Great Raid focused on the raid intertwined with a love story. Prince served as a consultant on the film, and believed it depicted the raid accurately.[204] [205] Marty Katz conveyed his interest in producing the pic: "This [rescue] was a massive operation that had very little chance of success. Information technology'south like a Hollywood film—information technology couldn't actually happen, but it did. That was why we were attracted to the material."[206] Another cover of the raid aired in December 2006 as an episode of the documentary serial Shootout!.[207]

Cabanatuan memorial images [edit]

-

The Park Memorial abreast the Main Monument and Sundial Museum

-

"60 minutes of the Great Rescue" Sundial Monument and Museum

-

Green entrance to the Memorial with mango trees

-

The interior of the Park

-

The names of the War Heroes in marble I

-

The names of the War Heroes in marble II

-

Another view of the green entrance to the Memorial

Encounter as well [edit]

- List of American guerrillas in the Philippines

- Military History of the Philippines during Globe War II

- Raid on Los Baños, February. 1945

- The Peachy Raid

- Margaret Utinsky

Notes [edit]

- ^ The states Armed services in the Far E, composed of the highly trained U.Southward. Army Philippine Scouts and the inadequately-trained Philippine Army

- ^ a b Breuer 1994, p. 31

- ^ a b McRaven 1995, p. 245

- ^ "WWII: Raid on the Bataan Expiry Camp". Shootout!. Season 2. Episode 5. Dec 1, 2006. 24:52 minutes in. History Aqueduct.

- ^ Breuer 1994, p. forty

- ^ a b Sides 2001, p. 134

- ^ Sides 2001, p. x

- ^ a b c Rottman 2009, p. 25

- ^ McRaven 1995, p. 247

- ^ Waterford 1994, p. 252

- ^ a b Carson 1997, p. 37

- ^ a b Alexander 2009, p. 231

- ^ a b Sides 2001, p. 169

- ^ "WWII: Raid on the Bataan Expiry Camp". Shootout!. Flavor ii. Episode 5. December one, 2006. 33:03 minutes in. History Channel.

- ^ Tenney, Lester I. (Jan one, 2001). My Hitch in Hell: The Bataan Expiry March. Potomac Books, Inc. ISBN9781597973465.

- ^ a b "Cabanatuan Camp". philippine-defenders.lib.wv.usa. Archived from the original on March iv, 2016. Retrieved September twenty, 2016.

- ^ Wodnik 2003, p. 39

- ^ Carson 1997, p. 62

- ^ Rottman 2009, p. 26

- ^ McRaven 1995, p. 248

- ^ a b King 1985, p. 61

- ^ Sides 2001, p. 20

- ^ Rottman 2009, p. half dozen

- ^ Norman & Norman 2009, p. 293

- ^ Breuer 1994, p. 55

- ^ Parkinson & Benson 2006, p. 132

- ^ Wright 2009, p. 64

- ^ Carson 1997, p. 81

- ^ Breuer 1994, p. 59

- ^ Wright 2009, p. 71

- ^ Sides 2001, p. 146

- ^ Breuer 1994, p. 97

- ^ Sides 2001, p. 187

- ^ Breuer 1994, p. 75

- ^ Breuer 1994, p. 74

- ^ Sides 2001, p. 160

- ^ Wright 2009, p. 70

- ^ a b Bilek & O'Connell 2003, p. 125

- ^ Breuer 1994, p. 125

- ^ a b c Breuer 1994, p. 56

- ^ Wright 2009, p. 58

- ^ Sides 2001, p. 149

- ^ a b Sides 2001, pp. 135–136

- ^ Wright 2009, p. 60

- ^ Wright 2009, p. 59

- ^ Wright 2009, p. 61

- ^ Parkinson & Benson 2006, p. 124

- ^ Sides 2001, p. 148

- ^ Wright 2009, p. 62

- ^ a b Sides 2001, pp. 142–143

- ^ Bilek & O'Connell 2003, p. 121

- ^ Breuer 1994, p. 137

- ^ Breuer 1994, p. 144

- ^ Sides 2001, p. 202

- ^ a b Breuer 1994, pp. 140–141

- ^ a b Sides 2001, pp. 237–238

- ^ Breuer 1994, p. 145

- ^ Sides 2001, pp. 243–244

- ^ McRaven 1995, p. 282

- ^ Sides 2001, pp. 245–246

- ^ Sides 2001, pp. 264–265

- ^ Reichmann, John A. (September 4, 1945). "Massacre of Americans is Charged". San Jose News . Retrieved March 15, 2010 – via Google News.

- ^ Sides 2001, p. 12

- ^ "General MacArthur Had Remarkable Military Career...52 Years". Eugene Register-Guard. Associated Printing. April 6, 1964. p. ii. Retrieved March xv, 2010 – via Google News.

- ^ a b Breuer 1994, pp. 120–121

- ^ Hunt 1986, p. 196

- ^ a b c d east f g Breuer 1994, pp. 148–149

- ^ Sides 2001, p. 261

- ^ Rottman 2009, p. x

- ^ a b Rottman 2009, p. 19

- ^ "WWII: Raid on the Bataan Expiry Camp". Shootout!. Flavor ii. Episode 5. December i, 2006. 29:20 minutes in. History Channel.

- ^ "WWII: Raid on the Bataan Expiry Military camp". Shootout!. Flavor two. Episode 5. December ane, 2006. 32:20 minutes in. History Aqueduct.

- ^ Breuer 1994, p. 150

- ^ a b Breuer 1994, p. 154

- ^ a b Breuer 1994, p. 3

- ^ Zedric 1995, p. 187

- ^ Sides 2001, p. 124

- ^ a b c d Breuer 1994, p. 158

- ^ a b Sides 2001, p. 73

- ^ a b Sides 2001, pp. 64–65

- ^ Breuer 1994, p. 157

- ^ Breuer 1994, p. 153

- ^ Rottman 2009, p. 22

- ^ Breuer 1994, p. 155

- ^ Black 1992, p. 280

- ^ Breuer 1994, p. 160

- ^ Sides 2001, p. 79

- ^ Alexander 2009, p. 237

- ^ a b Breuer 1994, p. 161

- ^ "WWII: Raid on the Bataan Death Camp". Shootout!. Flavor 2. Episode five. Dec 1, 2006. 32:42 minutes in. History Channel.

- ^ Sides 2001, p. 127

- ^ Sides 2001, p. 125

- ^ a b c Breuer 1994, p. 162

- ^ King 1985, p. 56

- ^ Sides 2001, p. 131

- ^ Sides 2001, p. 122

- ^ Alexander 2009, p. 241

- ^ Breuer 1994, p. 4

- ^ Sides 2001, p. 172

- ^ Sides 2001, p. 225

- ^ Sides 2001, p. 174

- ^ a b Sides 2001, p. 224

- ^ a b c d Breuer 1994, p. 165

- ^ a b c d Breuer 1994, p. 164

- ^ Sides 2001, p. 226

- ^ "WWII: Raid on the Bataan Death Camp". Shootout!. Flavor 2. Episode 5. December 1, 2006. 35:33 minutes in. History Channel.

- ^ Rottman 2009, p. 27

- ^ Sides 2001, pp. 179–180

- ^ Rottman 2009, p. 38

- ^ Sides 2001, p. 168

- ^ Hunt 1986, p. 198

- ^ a b Sides 2001, p. 176

- ^ Rottman 2009, p. 40

- ^ Sides 2001, p. 234

- ^ a b c Breuer 1994, p. 166

- ^ Sides 2001, p. 268

- ^ Rottman 2009, p. 43

- ^ a b c Sides 2001, pp. 248–250

- ^ "WWII: Raid on the Bataan Death Army camp". Shootout!. Season 2. Episode 5. December 1, 2006. 36:xx minutes in. History Channel.

- ^ Breuer 1994, p. 173

- ^ a b Sides 2001, p. 271

- ^ Breuer 1994, p. 174

- ^ Breuer 1994, p. 177

- ^ a b Alexander 2009, p. 248

- ^ Sides 2001, p. 269

- ^ a b Sides 2001, pp. 268–269

- ^ Breuer 1994, p. 178

- ^ Sides 2001, p. 275

- ^ "WWII: Raid on the Bataan Death Campsite". Shootout!. Season two. Episode 5. December 1, 2006. 41:44 minutes in. History Channel.

- ^ Sides 2001, p. 277

- ^ Sides 2001, p. 281

- ^ Sides 2001, p. 276

- ^ Zedric 1995, p. 192

- ^ Sides 2001, p. 283

- ^ Sides 2001, p. 285

- ^ a b Breuer 1994, pp. 182–183

- ^ Sides 2001, p. 284

- ^ Sides 2001, p. 291

- ^ Zedric 1995, p. 191

- ^ "WWII: Raid on the Bataan Death Campsite". Shootout!. Flavor ii. Episode 5. December i, 2006. 34:56 minutes in. History Channel.

- ^ a b Breuer 1994, p. 184

- ^ Sides 2001, p. 292

- ^ a b Sides 2001, p. 293

- ^ Sides 2001, p. 295

- ^ Breuer 1994, p. 185

- ^ Sides 2001, p. 297

- ^ a b Breuer 1994, p. 186

- ^ Sides 2001, p. 298

- ^ a b c Breuer 1994, p. 187

- ^ McRaven 1995, p. 271

- ^ a b Sides 2001, p. 299

- ^ a b Sides 2001, p. 222

- ^ a b c Breuer 1994, pp. 188–190

- ^ Sides 2001, p. 302

- ^ Rottman 2009, p. 54

- ^ a b Sides 2001, p. 300

- ^ a b Breuer 1994, pp. 194–195

- ^ a b Sides 2001, p. 327

- ^ a b c Zedric 1995, p. 198

- ^ Sides 2001, p. 310

- ^ Breuer 1994, p. 179

- ^ Breuer 1994, p. 191

- ^ a b Breuer 1994, p. 196

- ^ Sides 2001, pp. 306–307

- ^ Sides 2001, p. 314

- ^ Breuer 1994, p. 197

- ^ a b c Sides 2001, p. 326

- ^ Lessig, Hugh (July 6, 2011). "Another storied WWII veteran passes on". Daily Press Publisher Group. Archived from the original on July 7, 2011.

- ^ a b Zedric 1995, p. 195

- ^ a b Alexander 2009, p. 255

- ^ a b Rottman 2009, p. 61

- ^ a b c d Zedric 1995, p. 199

- ^ a b Johnson 2002, p. 264

- ^ Goff, Marsha Henry (May 23, 2006). "Rangers Played Heroic Role in Camp Liberation". Lawrence Journal-Globe. Archived from the original on August 4, 2010. Retrieved March 29, 2010.

- ^ a b c Breuer 1994, p. 211

- ^ McRaven 1995, p. 249

- ^ Kelly 1997, p. 33

- ^ a b Breuer 1994, p. 180

- ^ Kerr 1985, p. 246

- ^ Sides 2001, p. 316

- ^ Zedric 1995, p. 193

- ^ Alexander 2009, p. 253

- ^ Breuer 1994, p. 207

- ^ Sides 2001, p. 324

- ^ Sides 2001, p. 329

- ^ Rottman 2009, p. 56

- ^ "Visitor is Thrilled to Get Word Son Among Yanks Rescued From Cabanatuan". Leningrad Times. Feb 6, 1945. Retrieved March 15, 2010 – via Google News.

- ^ Breuer 1994, p. 202

- ^ Hogan 1992, p. 88

- ^ Sides 2001, p. 328

- ^ McDaniel, C. Yates (February v, 1945). "3,700 Internees, Mostly Americans, Freed From Camp in Eye of Manila". Toledo Blade . Retrieved July 26, 2011.

- ^ Parrott, Lindesay (February 6, 1945). "Japanese Cutting Off" (Fee required). The New York Times . Retrieved July 26, 2011.

- ^ Alexander 2009, p. 270

- ^ King 1985, p. 71

- ^ O'Donnell 2003, p. 178

- ^ a b Breuer 1994, p. 205

- ^ Alexander 2009, p. 6

- ^ a b Johnson 2002, p. 276

- ^ Sides 2001, p. 334

- ^ a b Rottman 2009, p. 62

- ^ Carson 1997, p. 247

- ^ Breuer 1994, p. 206

- ^ Pullen, Randy (Baronial 18, 2005). "Dandy Raid on Cabanatuan depicts Warrior Ethos". The Fort Elation Monitor. Archived from the original on June 3, 2008. Retrieved February 21, 2010.

- ^ Barber, Mike (August 25, 2005). "Leader of WWII's "Dandy Raid" looks dorsum on real-life Pow rescue". Seattle Postal service-Intelligencer. Archived from the original on August 4, 2010. Retrieved March fifteen, 2010.

- ^ Hui Hsu, Judy Chia (August twenty, 2005). ""The Bang-up Raid" includes Seattle native who helped salvage POWs". The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on August 4, 2010. Retrieved June 20, 2010.

- ^ Tariman, Pablo A. (February 9, 2005). "Near Successful Rescue Mission in United states History". Philippine Daily Inquirer . Retrieved March fifteen, 2010.

- ^ Lam, Jeff; Larioza, Nito; Sessions, David; Thompson, Erik (December 1, 2006), WWII: Raid on the Bataan Death Camp , retrieved April xx, 2017

References [edit]

- Alexander, Larry (2009). Shadows in the Jungle: The Alamo Scouts Backside Japanese Lines in World War II. Penguin Grouping. ISBN978-0-451-22593-ane.

- Bilek, Tony; O'Connell, Gene (2003). No Uncle Sam: The Forgotten of Bataan. Kent, Ohio: Kent State University Press. ISBN0-87338-768-vi.

- Black, Robert W. (1992). Rangers in Globe War Ii. Random House. ISBN0-8041-0565-0.

- Breuer, William B. (1994). The Great Raid on Cabanatuan. New York: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN0-471-03742-7.

- Carson, Andrew D. (1997). My Time in Hell: Memoir of an American Soldier Imprisoned By the Japanese in Earth State of war II. McFarland & Company. ISBN0-7864-0403-5.

- Hogan, David W. (1992). Raiders or Aristocracy Infantry?: The Irresolute Office of the U.Due south. Army Rangers from Dieppe to Grenada. ABC-CLIO. ISBN0-313-26803-7.

- Hunt, Ray C. (1986). Behind Japanese Lines: An American Guerrilla in the Philippines. University Printing of Kentucky. ISBN0-8131-0986-eight.

- Johnson, Forrest Bryant (2002). Hour of Redemption: The Heroic WWII Saga of America's Virtually Daring Pow Rescue. Warner Books. ISBN0-446-67937-ii.

- Kelly, Arthur Fifty. (1997). BattleFire!: Gainsay Stories from World War Two. University Printing of Kentucky. ISBN0-8131-2034-9.

- Kerr, Due east. Bartlett (1985). Give up & Survival: The Feel of American POWs in the Pacific 1941–1945. William Morrow and Visitor. ISBN0-688-04344-v.

- Rex, Michael J. (1985). Rangers: Selected Combat Operations in World State of war Two. DIANE Publishing. ISBN1-4289-1576-one.

- McRaven, William H. (1995). Spec Ops: Case Studies in Special Operations Warfare Theory and Practice. New York: Presidio Printing. ISBN0-89141-544-0.

- Norman, Michael; Norman, Elizabeth M. (2009). Tears in the Darkness: The Story of the Bataan Death March and Its Aftermath. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN978-0-37427-260-9.

- O'Donnell, Patrick K. (2003). Into the Rising Sun: In Their Own Words, World War II'south Pacific Veterans Reveal the Middle of Combat. Simon & Schuster. ISBN0-7432-1481-1.

- Parkinson, James West.; Benson, Lee (2006). Soldier Slaves: Abandoned past the White House, Courts, and Congress. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Plant Press. ISBN1-59114-204-0.

- Rottman, Gordon (2009). The Cabanatuan Prison Raid – The Philippines 1945. Osprey Publishing; Osprey Raid Series #3. ISBN978-1-84603-399-v.

- Sides, Hampton (2001). Ghost Soldiers: The Forgotten Ballsy Story of Globe War II's Most Dramatic Mission. New York: Doubleday. ISBN0-385-49564-1.

- Waterford, Van (1994). Prisoners of the Japanese in World War 2. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Visitor. ISBN0-89950-893-six.

- Wodnik, Bob (2003). Captured Honor. Pullman, Washington: Washington State University Press. ISBN0-87422-260-5.

- Wright, John Thousand. (2009). Captured on Corregidor: Diary of an American P.O.W. in World State of war II. McFarland & Company. ISBN978-0-7864-4251-5.

- Zedric, Lance Q. (1995). Silent Warriors of World War 2: The Alamo Scouts Behind Japanese Lines. Ventura, California: Pathfinder Publishing of California. ISBN0-934793-56-5.

External links [edit]

- Cabanatuan American Memorial

- Alamo Scouts Website

- LIFE 'south unpublished photos of the aftermath of the raid

- U.Southward.–Japanese Dialogue on POWs

- Booknotes interview with Hampton Sides on Ghost Soldiers: The Forgotten Epic Story of World War II'due south Most Dramatic Mission, September 30, 2001.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Raid_at_Cabanatuan

0 Response to "Hius 222 Book Review Paper Escape From Bataan"

Postar um comentário